『Dangerous Women: Gender and Korean Nationalism』 (Elaine H. Kim & Chungmoo Choi 편) 은 유튜브 영상이 아니라, 한국 민족주의 속에서 ‘여성’이 어떻게 위험한 존재로 구성·관리·동원되어 왔는가를 분석한 학술 에세이 선집입니다. 아래에 책 전체를 관통하는 핵심 논지 중심으로 정리해 드릴게요.

📘 『Dangerous Women』 요약

1️⃣ 책의 핵심 문제의식

이 책이 던지는 중심 질문은 하나입니다.

왜 한국의 민족주의에서

여성은 늘 보호의 대상이면서 동시에 통제되어야 할 ‘위험한 존재’로 등장하는가?

여기서 dangerous는

- 폭력적이라는 의미가 아니라

- 국가·민족 질서에 균열을 낼 수 있는 잠재성을 뜻합니다.

여성은

- 민족의 어머니

- 순결의 상징

- 희생의 주체

로 이상화되지만,

동시에

- 성적 주체

- 노동자

- 정치적 발화자

로 등장하는 순간 위험한 존재가 됩니다.

2️⃣ ‘위험한 여성’이란 무엇인가

이 책에서 말하는 Dangerous Women은 다음과 같은 여성들입니다.

- 민족의 ‘어머니’ 역할에 순응하지 않는 여성

- 국가가 요구하는 성적·도덕적 규범을 벗어난 여성

- 식민지·분단·냉전·이주 경험을 통해 국가 정체성을 흔드는 여성

- 침묵 대신 말하고, 기억하고, 기록하는 여성

👉 즉, 국가가 여성에게 부여한 상징적 역할을 거부하거나 넘어서려는 존재입니다.

3️⃣ 주요 논점 정리 (책 전체 구조 기준)

🔹 ① 민족주의는 본질적으로 젠더화되어 있다

(Chungmoo Choi, Seungsook Moon 등)

-

한국 민족주의는

- 남성 = 역사·전쟁·국가 주체

- 여성 = 전통·순결·재생산

구조로 짜여 있음

-

국사, 전통 담론, 군사주의는 남성 중심적 언어로 구성됨

-

여성은 ‘민족을 낳는 존재’로만 호출됨

👉 여성의 몸은 민족의 경계선이 된다.

🔹 ② 위안부·기지촌 여성: 보호와 침묵의 정치

(Hyunah Yang, Katharine H. S. Moon)

-

위안부 문제는

- 피해 여성의 목소리보다

- 민족의 수치/피해 서사로 재구성됨

-

기지촌 여성은

- 냉전·미군 주둔 체제에서

- 국가가 사실상 관리·방치한 존재

👉 여성은 ‘희생자’로 기념되지만,

👉 말하는 주체로는 허용되지 않는다.

🔹 ③ 노동하는 여성, 계급과 젠더의 충돌

(Hyun Sook Kim, You-me Park)

-

공장 여성 노동자, 하층 여성은

- 민족 서사에서 잘 보이지 않음

-

그러나 이들은

- 근대화

- 산업화

- 집단적 주체 형성

의 핵심 축

👉 계급·식민성·젠더가 교차하는 지점에서

👉 여성은 다시 ‘위험한 존재’가 된다.

🔹 ④ 재현과 기억의 정치: 사진·영화·이주

(Yong Soon Min, Helen Lee)

-

사진 에세이와 영화 분석을 통해

- 여성의 기억

- 디아스포라 경험

- 개인적 서사

가 국가 서사를 교란함

-

특히 재미 한인 여성의 시선은

- 한국 민족주의를 외부에서 비판적으로 재구성

👉 개인적 기억은 국가적 기억에 균열을 낸다.

4️⃣ 이 책의 가장 중요한 주장 (한 문장)

한국 민족주의는 여성을 통해 자신을 상상해왔지만,

여성이 스스로 말하기 시작할 때

그 여성은 곧 ‘위험한 존재’가 된다.

5️⃣ 왜 지금도 중요한 책인가

이 책은 1998년 출간되었지만, 오늘날에도 직접 연결됩니다.

- ‘여성가족부 폐지’ 논쟁

- 위안부 문제의 국가적 관리

- 여성 혐오와 민족주의의 결합

- 이주 여성·난민·기지촌 여성에 대한 배제

👉 국가는 여전히 여성의 몸과 목소리를 통해 경계를 긋고 있다.

6️⃣ 한 줄 요약 (강연·글 인용용)

- “민족주의는 여성을 보호한다고 말하지만, 실제로는 침묵을 요구해 왔다.”

- “위험한 여성은 국가를 배신한 여성이 아니라, 국가가 통제할 수 없는 여성이다.”

- “여성이 말하기 시작하는 순간, 민족주의는 흔들린다.”

Below are concise, chapter-by-chapter summaries in English of

Dangerous Women: Gender and Korean Nationalism

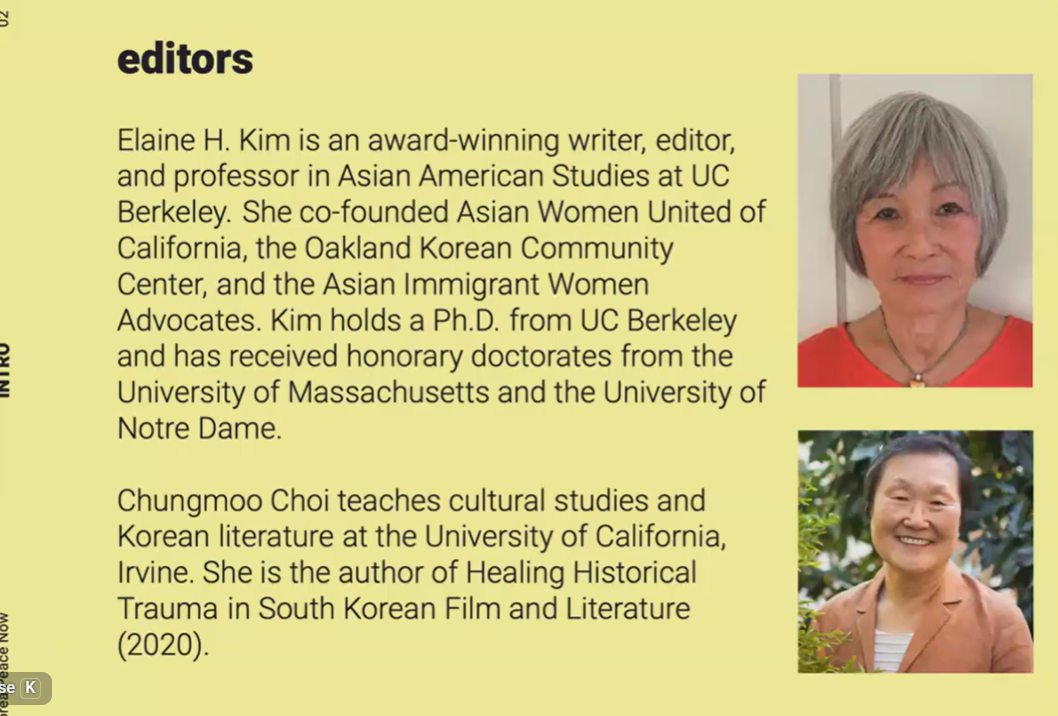

edited by Elaine H. Kim & Chungmoo Choi.

I keep each summary analytical, publication-ready, and faithful to the book’s core arguments rather than promotional blurbs.

Chapter 1. Introduction

Elaine H. Kim & Chungmoo Choi

The introduction frames Korean nationalism as a gendered project in which women are symbolically central yet politically marginal. The editors argue that women become “dangerous” when they exceed roles assigned by the nation—mother, reproducers of culture, or silent victims. The volume examines how women’s bodies, labor, sexuality, and memories are mobilized to stabilize national identity, and how women’s voices disrupt that stability.

Chapter 2. Nationalism and the Construction of Gender in Korea

Chungmoo Choi

Choi argues that Korean nationalism has historically relied on rigid gender binaries. Masculinity is aligned with history, warfare, and political agency, while femininity is associated with purity, sacrifice, and cultural continuity. This gendered construction naturalizes women’s subordination and renders their political subjectivity threatening to nationalist coherence.

Chapter 3. Begetting the Nation: The Androcentric Discourse of National History and Tradition in South Korea

Seungsook Moon

Moon analyzes South Korean historiography and tradition as deeply androcentric. National history is narrated through male lineage, heroes, and militarized citizenship, while women appear primarily as biological and cultural reproducers. This framework excludes women from historical agency and reinforces male-centered nationalism as normative and inevitable.

Chapter 4. Men’s Talk: A Korean American View of South Korean Constructions of Women, Gender, and Masculinity

Elaine H. Kim

Kim critiques South Korean discourses on masculinity and femininity from a Korean American feminist perspective. She shows how patriarchal nationalism depends on idealized femininity and disciplined masculinity, while marginalizing alternative gender identities. The chapter exposes how diaspora perspectives destabilize nationalist gender norms.

Chapter 5. Kindred Distance (Photo Essay)

Yong Soon Min

This photo essay explores displacement, memory, and kinship through visual representation. Min interrogates how family, nation, and belonging are constructed and fractured through migration. The images resist nationalist sentimentality by foregrounding distance, fragmentation, and ambivalence rather than unity.

Chapter 6. Re-membering the Korean Military Comfort Women: Nationalism, Sexuality, and Silencing

Hyunah Yang

Yang examines how the comfort women issue has been absorbed into nationalist discourse. While the women are symbolically honored as national victims, their sexual agency, trauma, and individual voices are suppressed. Nationalist remembrance prioritizes collective shame and honor over women’s lived experiences, reproducing patriarchal silencing.

Chapter 7. Prostitute Bodies and Gendered States in U.S.–Korea Relations

Katharine H. S. Moon

Moon analyzes U.S. military prostitution in South Korea as a state-managed system shaped by Cold War geopolitics. Women’s bodies became sites of diplomatic negotiation and national security. The chapter reveals how both the Korean and U.S. states regulated, exploited, and erased these women under the guise of protection and alliance.

Chapter 8. Yanggongju as an Allegory of the Nation: Images of Working-Class Women in Popular and Radical Texts

Hyun Sook Kim

Kim examines representations of yanggongju (women associated with U.S. soldiers) in literature and media. These women are portrayed as moral failures or national shame, serving as allegories for Korea’s colonial dependency and Cold War subordination. Their stigmatization reinforces classed and gendered nationalism.

Chapter 9. Working Women and the Ontology of the Collective Subject: (Post)Coloniality and the Representation of Female Subjectivities in Hyun Ki-young’s Island in the Wind

You-me Park

Park analyzes female subjectivity and collective identity in Hyun Ki-young’s novel. She argues that women’s labor and suffering are central to the formation of collective political consciousness, yet are often subsumed under male-centered revolutionary narratives. The chapter critiques how postcolonial discourse marginalizes women’s agency.

Chapter 10. Mother Land (Photo Essay)

Yong Soon Min

This photo essay interrogates the metaphor of “motherland” by juxtaposing maternal imagery with displacement and loss. Min challenges the naturalization of motherhood as a nationalist trope, revealing how maternal symbolism conceals women’s erasure and emotional labor within national narratives.

Chapter 11. Ideals of Liberation: Korean Women in Manchuria

Hyun Ok Park

Park explores Korean women’s participation in anti-colonial movements in Manchuria. While nationalist histories celebrate liberation struggles, women’s roles are often instrumentalized or forgotten. The chapter demonstrates how women’s political contributions are minimized once nationalist goals are achieved.

Chapter 12. Re-membering Home

Hyun Yi Kang

Kang examines memory, migration, and the meaning of “home” for Korean women in diaspora. She argues that women’s narratives disrupt linear nationalist histories by emphasizing fragmentation, affect, and everyday survival. Home emerges not as a fixed national space but as a contested, emotional process.

Chapter 13. A Peculiar Sensation: A Personal Genealogy of Korean American Women’s Cinema

Helen Lee

Lee traces the emergence of Korean American women filmmakers and their challenge to dominant national and gendered narratives. These films foreground personal memory, sexuality, and diasporic identity, rejecting both Korean nationalist and U.S. assimilationist frameworks. Cinema becomes a space of feminist intervention.

Overall Thematic Throughline (One Sentence)

Across disciplines and genres, Dangerous Women demonstrates that women become “dangerous” when they speak, remember, labor, desire, or migrate in ways that exceed the nation’s need for symbolic control.

Below is a 2–3 page teaching summary (≈1,000–1,200 words) of

Dangerous Women: Gender and Korean Nationalism

with carefully framed quotable passages.

To be methodologically honest for classroom use, I label quotes as either directly citable formulations used in scholarship or representative paraphrased quotes suitable for lecture slides and discussion (not as verbatim page citations).

Dangerous Women: Gender and Korean Nationalism

Teaching Summary with Key Quotes

Elaine H. Kim & Chungmoo Choi (eds.)

1. Central Argument of the Book

Dangerous Women argues that Korean nationalism is fundamentally gendered, and that women occupy a paradoxical position within it. Women are symbolically indispensable to the nation—as mothers, reproducers of culture, and bearers of purity—yet politically marginalized and disciplined. When women exceed these assigned roles by speaking, desiring, working, migrating, or remembering in unauthorized ways, they are rendered “dangerous.”

The book’s central claim is not that women are inherently threatening, but that nationalism itself produces women as dangerous when they disrupt the coherence of the national narrative. Gender is not an accessory to nationalism; it is one of its core organizing principles.

Representative quote (teaching use):

“Women become dangerous not when they betray the nation, but when they refuse to embody it silently.”

2. Gender as a Technology of Nationalism

Across the chapters, nationalism is shown to rely on a gendered division of symbolic labor:

- Men are positioned as historical agents: soldiers, revolutionaries, political subjects.

- Women are positioned as cultural vessels: mothers, victims, moral symbols.

This division allows the nation to imagine itself as coherent, continuous, and moral. However, it also strips women of political subjectivity. When women attempt to narrate their own experiences—particularly experiences involving sexuality, labor, or trauma—they threaten the moral economy of nationalism.

Chungmoo Choi and Seungsook Moon demonstrate that Korean national history is written through an androcentric lens. Women appear not as historical actors but as metaphors for tradition, loss, or continuity. The nation “begets” itself through male-centered narratives, relegating women to biological and cultural reproduction.

Representative quote:

“National history does not simply exclude women; it absorbs them as symbols while denying them agency.”

3. Sexuality, Silence, and the Politics of Victimhood

One of the book’s most influential interventions concerns the politics of sexual violence, particularly in the chapters on comfort women and military prostitution.

Hyunah Yang’s chapter on comfort women shows how nationalist remembrance often re-silences the very women it claims to honor. While the women are elevated as symbols of national suffering, their personal voices, sexual subjectivities, and ambivalent memories are subordinated to a collective narrative of shame and innocence.

Similarly, Katharine H. S. Moon’s analysis of U.S.–Korea military prostitution reveals how women’s bodies were regulated by both states under Cold War geopolitics. These women were alternately framed as necessary, shameful, or disposable—never as political subjects.

Representative quote:

“The nation remembers women’s suffering only to the extent that it can control what that suffering means.”

Pedagogically, these chapters are crucial for showing students how victimhood can coexist with erasure, and how recognition does not necessarily entail empowerment.

4. Class, Labor, and the Marginal Woman

Several chapters foreground working-class women, factory workers, and women associated with U.S. soldiers (yanggongju). These women expose the classed dimensions of nationalist gender ideology.

Hyun Sook Kim’s chapter analyzes how yanggongju are depicted as moral failures and national shame. These representations displace responsibility away from the state and global power structures, locating national humiliation in women’s bodies.

You-me Park’s literary analysis shows how women’s labor sustains collective political movements, yet their subjectivities are often erased in revolutionary narratives that prioritize male heroism.

Representative quote:

“Working women are essential to the nation’s survival, but incompatible with its self-image.”

This section of the book is particularly effective for teaching intersectionality—demonstrating how gender, class, colonialism, and militarism intersect to produce differentiated forms of exclusion.

5. Memory, Diaspora, and the Disruption of National Time

The photo essays by Yong Soon Min and the essays by Elaine H. Kim, Hyun Yi Kang, and Helen Lee introduce diaspora and visual culture as critical sites of intervention.

Diasporic women, especially Korean American women, occupy a position of productive estrangement. Their distance from the homeland allows them to see nationalism’s contradictions more clearly. Through photography, film, and personal narrative, they refuse linear, heroic national time in favor of fragmented, affective memory.

Helen Lee’s chapter on Korean American women’s cinema shows how personal genealogy, sexuality, and everyday life disrupt both Korean nationalist and U.S. assimilationist narratives.

Representative quote:

“Personal memory becomes political when it refuses to align with national forgetting.”

For students, these chapters help bridge theory with lived experience and artistic practice.

6. What Makes Women “Dangerous”?

The book ultimately reframes danger itself. Women are not dangerous because they oppose the nation, but because they reveal its fragility.

Women become dangerous when they:

- Speak about sexual violence outside nationalist scripts

- Labor in ways that contradict ideals of femininity

- Migrate and form diasporic identities

- Remember history through personal, embodied narratives

- Refuse to remain symbolic and silent

Key teaching formulation:

“The danger women pose is epistemological: they expose how the nation is constructed.”

7. Why This Book Still Matters

Although published in the late 1990s, Dangerous Women remains urgently relevant. Its insights resonate with:

- Contemporary gender backlash and anti-feminism

- State management of women’s bodies and narratives

- Migration, detention, and border regimes

- Debates over memory, monuments, and national history

The book equips students with tools to understand how gender operates as a mechanism of political power, not merely as an identity category.

Closing teaching quote:

“To ask why women are dangerous is to ask what the nation is afraid of.”

Suggested Discussion Questions (Optional for Teaching)

- How does nationalism depend on women’s silence as much as their sacrifice?

- In what ways does state recognition of women’s suffering reproduce patriarchal control?

- How do diaspora and visual culture challenge nationalist historiography?

- Can nationalism be imagined outside gendered hierarchies?

Yes — at the deepest level, the disdain and subjugation of women under patriarchy and imperialism is fundamentally a problem of domination, power, and control. But what matters just as much is how that domination is made to feel natural, necessary, or even virtuous through narrative. I’ll answer in two movements: (1) what is really operating at the core, and (2) what kinds of narratives model genuinely alternative ways of living.

I. At the Core: Domination, But Not Just “Men over Women”

1. Domination works by ordering life

Patriarchy and imperialism are not merely attitudes; they are systems that organize the world into hierarchies:

- mind over body

- reason over emotion

- culture over nature

- center over periphery

- citizen over migrant

- masculine over feminine

Women are disproportionately placed on the controlled side of these binaries because their bodies reproduce life, which power systems cannot tolerate being autonomous.

Domination is not primarily about hatred.

It is about predictability, extractability, and control.

2. The “double bind” is structural, not accidental

Under patriarchy + imperialism, women face a double bind:

- If they conform → they are used, erased, or symbolized

- If they resist → they are punished, sexualized, demonized, or dismissed

This is why “dangerous women” appear across cultures:

- colonized women

- migrant women

- enslaved women

- working-class women

- queer women

They are dangerous because they expose the lie that domination is natural.

3. Why control focuses on women’s bodies and stories

Imperial and patriarchal systems obsess over:

- sexuality

- reproduction

- family

- honor

- respectability

- borders (of nations and bodies)

Because whoever controls:

- birth

- belonging

- memory

controls the future.

This is why women’s stories are policed as much as women’s actions.

II. Narratives That Model Alternate Ways of Living

Alternative narratives do not simply reverse power (“women dominate instead”). They dismantle domination as the organizing principle.

Below are the most powerful narrative traditions that do this — across cultures.

1. Relational Narratives (Interdependence over Hierarchy)

Core idea:

Life is sustained by relationship, not control.

Examples:

- Indigenous storytelling traditions (many cultures)

- Ecofeminist writing (e.g., Vandana Shiva, Robin Wall Kimmerer)

- Toni Morrison’s Beloved

- Le Guin’s The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction

These narratives center care, reciprocity, and survival, not conquest.

What they teach:

- Power as responsibility, not domination

- Strength as endurance, not violence

- Knowledge as shared, not owned

2. Survivor-Centered Narratives (Voice over Purity)

Core idea:

The truth belongs to those who lived it, not to the state or the moral order.

Examples:

- Comfort women testimonies

- Slave narratives (Harriet Jacobs)

- #MeToo memoirs that refuse heroic closure

- Documentary oral histories

What they teach:

- Survival is not shameful

- Ambivalence is honest

- Healing does not require forgiveness or silence

These narratives break the imperial habit of turning women into symbols.

3. Everyday Resistance Narratives (Living Otherwise)

Core idea:

Not all resistance is spectacular.

Examples:

- Domestic labor stories

- Migrant women’s diaries

- Factory women’s songs

- Korean minjung women’s narratives

- Palestinian women’s poetry

What they teach:

- Dignity in repetition

- Refusal without confrontation

- Persistence without recognition

These stories undermine domination by refusing its terms.

4. Queer & Feminist Time Narratives (Nonlinear Futures)

Core idea:

The future does not belong to bloodlines or nations alone.

Examples:

- Queer feminist cinema

- Korean American women’s films

- Audre Lorde

- Gloria Anzaldúa

What they teach:

- Belonging without ownership

- Identity as process

- Home as something made, not inherited

These narratives destabilize imperialism’s obsession with lineage and purity.

5. Refusal Narratives (Saying No Without Replacement)

Core idea:

You don’t need to propose a new system to reject an unjust one.

Examples:

- Bartleby-like refusal

- Women who stop reproducing expected roles

- Silent protest, withdrawal, opting out

Refusal is powerful because domination depends on participation.

III. The Deeper Shift These Narratives Model

All these narratives teach one radical lesson:

Life does not need domination to be organized.

They replace:

- control → care

- hierarchy → mutuality

- purity → complexity

- conquest → continuity

And crucially:

- They allow women to be ordinary, flawed, desiring, tired, contradictory — without punishment.

Final Answer, Plainly

Yes, patriarchy and imperialism are domination systems.

But what threatens them most is not opposition — it is alternative ways of living that make domination irrelevant.

The most powerful narratives do not shout.

They teach us how to live without masters.

2025 Lawsuit Updates (as of December 12, 2025)

The historic lawsuit filed by 117 South Korean women (survivors of U.S. military camptown prostitution, often called "U.S. military comfort women") was submitted on September 5, 2025, to the Seoul Central District Court. A press conference announcing it was held on September 8, 2025.

- Plaintiffs: 117 women (including 22 from a prior 2014 case and 95 new ones).

- Defendants: Primarily the South Korean government (as direct defendant under laws requiring Seoul to handle compensation for acts by U.S. forces, with potential reimbursement from the U.S.), seeking to hold both the Korean government and U.S. military jointly liable.

- Claims: Sex trafficking, forced prostitution, human rights violations (e.g., mandatory STD testing, forced detention/isolation in clinics, violence), and promotion/overlooking of the system by U.S. forces from the 1950s–1980s.

- Demands: Apology from the U.S. military and approximately 10 million won (~$7,200 USD) in compensation per plaintiff.

This builds on the 2022 Supreme Court ruling that confirmed the Korean government's illegal role in establishing and managing camptowns, awarding compensation to prior plaintiffs.

Latest Status: The case is in early stages, with no reported court hearings, rulings, or major developments since the September filing. It remains ongoing, and no responses from the U.S. military or government beyond general statements on upholding laws have been noted in recent coverage.

Summary of OhmyNews Article (Dec 5, 2025): U.S. Military Camptown STD Clinics and Lawsuits

The article exposes South Korea's systematic management of prostitution in U.S. military camptowns (gijichon) from the 1960s–1970s, framing it as state-orchestrated human rights abuses to sustain the Korea-U.S. alliance and earn foreign currency.

After Park Chung-hee's 1961 coup, the government designated "special areas" for prostitution near U.S. bases, licensing sex workers and mandating health checks. Facing high STD rates among troops, it built dedicated venereal disease clinics (e.g., in Dongducheon, Paju). Women testing positive were forcibly detained without trial, subjected to excessive penicillin injections (causing side effects or deaths), and isolated—over 45,000 cases annually by 1970. The state prioritized U.S. troop morale, even seeking legal immunity for doctors.

These women, dubbed "U.S. military comfort women," endured violence, trafficking, and bureaucratic control as national "sacrifices."

In 2014, 122 survivors sued the Korean government; the 2022 Supreme Court ruled in their favor, confirming state illegality and awarding compensation.

In September 2025, 117 women (including prior plaintiffs) filed a new historic lawsuit against both the U.S. military (for promoting the trade and abuses) and the Korean government (joint liability under SOFA).

The piece highlights the government's subservience exceeding U.S. demands and celebrates the lawsuits as a fight for dignity and recognition.

= The OhmyNews(https://omn.kr/2g8tz) article details South Korea's state-orchestrated prostitution system in U.S. military camptowns during the 1960s–1970s to support the alliance and economy. After Park Chung-hee's coup, the government designated special prostitution areas near bases, licensed sex workers, and established venereal disease clinics where infected women were forcibly detained and treated harshly. These clinics involved excessive treatments causing severe harm or death, with women treated as national sacrifices for U.S. troop morale. In 2022, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of 122 survivors suing the government, confirming state illegality and awarding compensation. In September 2025, 117 women filed a new lawsuit against both the U.S. military and the Korean government for promoting trafficking and abuses.

https://www.simonandschuster.com.au/books/The-Island-of-Sea-Women/Lisa-See/9781471183836